Detailed overview of Ethereum 2.0 shard chains: Committees, Proposers and Attesters

Many details of how Ethereum 2.0 will work are available today, and multiple teams are already working on implementations of it. One large component for which neither spec nor any detailed info is available today is the shard chains. Ultimately the spec will appear here, but in the meantime I will provide a detailed overview in this blog post.

Footnote: an earlier version of this write-up was describing a now obsolete version of Ethereum’s approach called IMD (immediate message driven). That version can be found here.

Committees and their formation

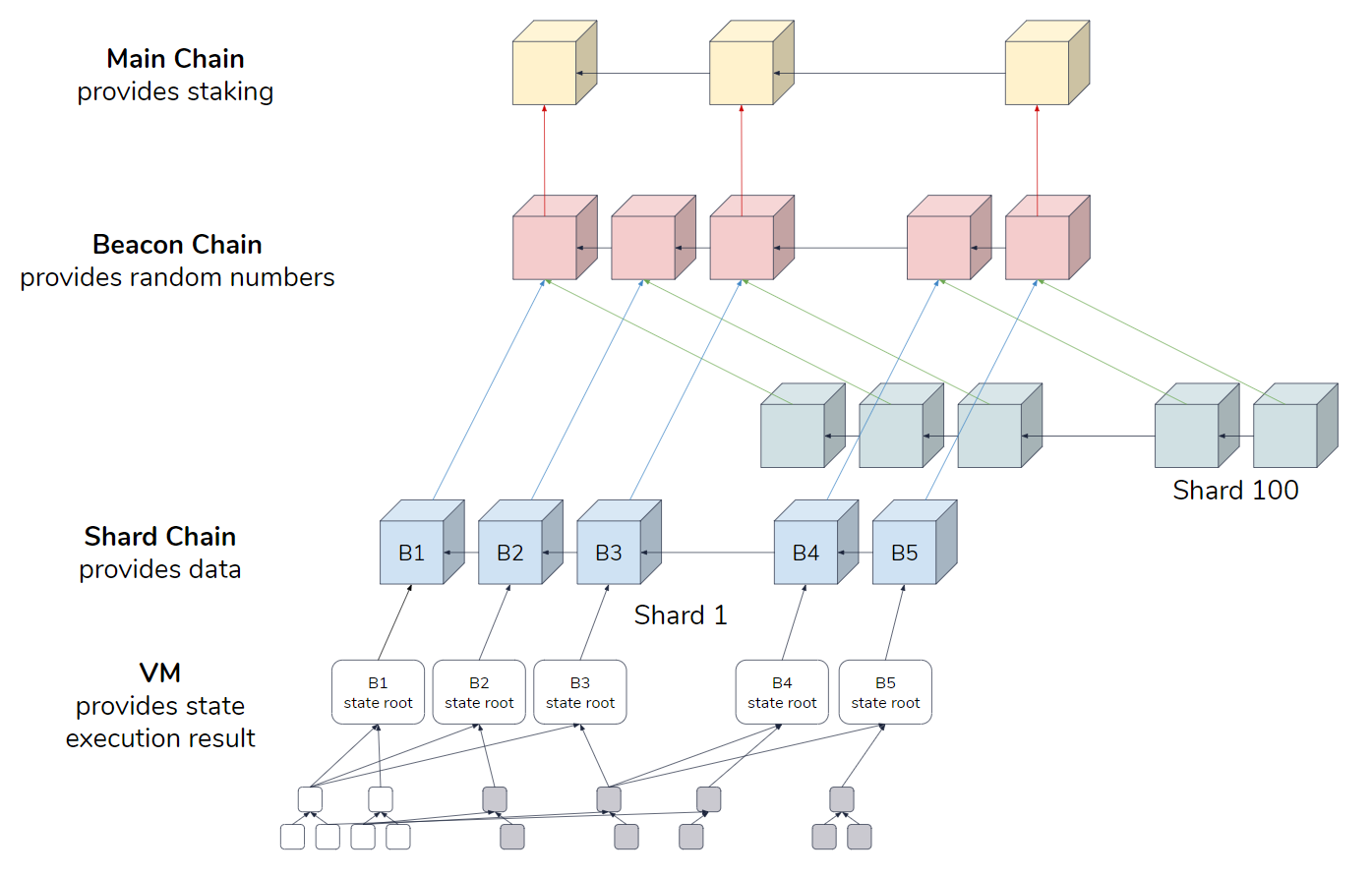

Any participant of Ethereum network can become a validator, for which it is sufficient to stake 32 ETH into a dedicated smart contract on the existing Proof-of-Work chain.

Once a participant is in a validator pool, they can be assigned to a certain shard. The assignment is completely random, and leverages a smart usage of Verifiable Delay Functions (VDFs) to achieve unbiased randomness.

If one stakes significantly more than 32 ETH (say 320 ETH), they get proportional number of validator seats. Those seats are in no way connected to each other, in particular each of them is assigned to a shard independently, and thus in the worst case a participant that staked 320 ETH could at any single moment be a validator in 10 shards. Not doing so would increase the likelihood of an adversary overtaking a shard, and there’s an expectation that higher stakes generally mean access to more resources, and thus more compute power.

Block production in a proof-of-stake system

Ethereum 2.0 is a proof-of-stake system. In this section I will review a general framework of how blocks are created in many existing and proposed proof-of-stake blockchains:

In such a framework, blocks are produced at a regular schedule, say once every 5 seconds. There’s a set of validators that produce and validate blocks. For each 5 seconds time slot one validator is assigned who is expected to produce a block at that time slot. If validators have non-equal stakes, validators with larger stakes generally have more time slots in which they propose blocks.

When forks appear, the selected chain that an honest validator is expected to build upon is the one that has the most blocks in it. For as long as the honest members control more than half of all the validators, it is expected that reversing a large chain of blocks is very hard. Even if the entirety of the dishonest minority intentionally chooses not to produce blocks during their time slots on the honest chain, and concurrently secretly builds a fork chain, their chain is expected to be shorter than the honest chain, an argument similar to that in proof-of-work systems, for as long as more than half of the hash power is controlled by honest participants, the probability of reversing a long tail of blocks is very unlikely.

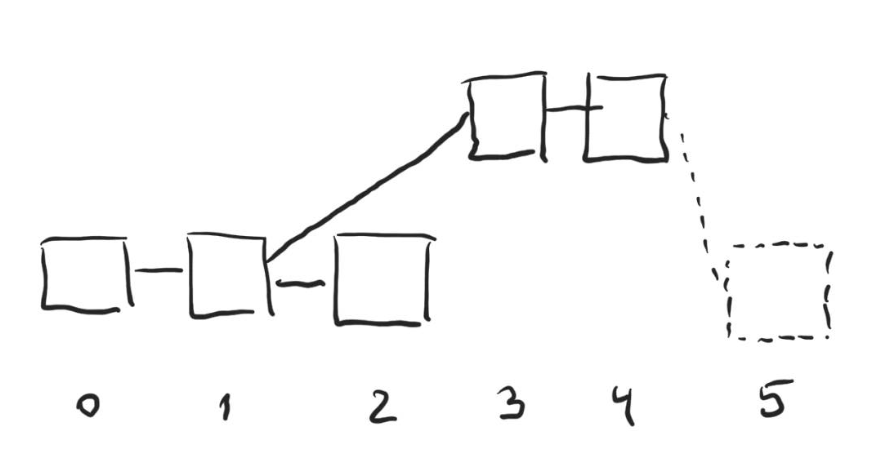

However, such framework, if implemented naively, has a multitude of issues. First, short term forks are still very possible. If the minority controls just 10% of all the validators, the probability of reversing even the last say 6 blocks becomes prohibitively high. Second, all sorts of censoring problems arise. For example, if dishonest participants happen to have two slots in a row, they can censor the block in the slot immediately preceding theirs:

On the figure above dishonest validators control time slots 3 and 4. They intentionally produce their blocks on top of the block from time slot 1, effectively censoring the block in time slot 2. The honest validator in slot 5 will choose the longer chain that 3 and 4 have built when produce their block.

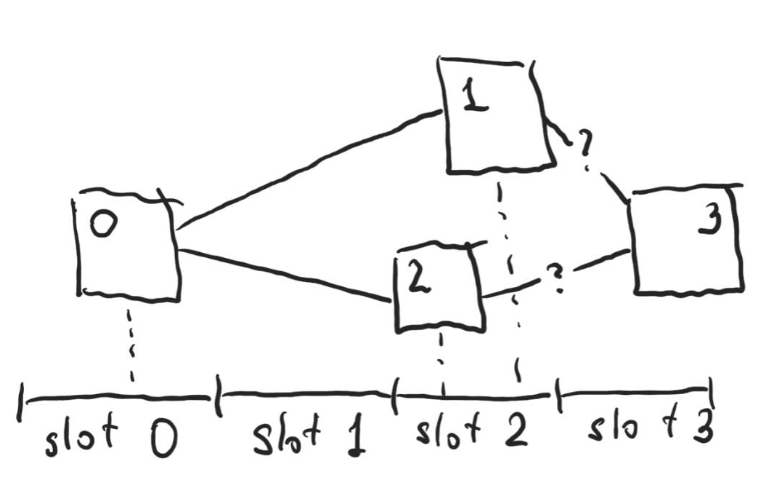

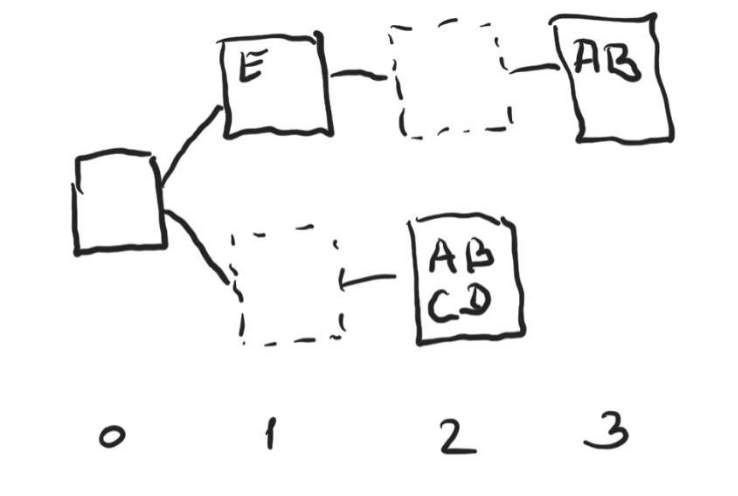

A single dishonest validator can also attempt to censor the block from the previous time slot. Consider the following figure. The X-axis is time, with time slots for each validator labeled at the bottom. The number on each block is the slot at which the block was expected to be published. Honest validators assigned to slots 0 and 2 have published their blocks in time, but the dishonest validator assigned to slot 1 delayed their block and only published it after the block for time slot 2 was published (thus the validator in time slot 2 was not aware of the block and built their block on top of block in time slot 0):

What block shall honest validator at slot 3 built upon? Consider 4 possible rules:

- Always build on the block from the earlier slot. This way a dishonest validator in the earlier slot can delay publishing their block until the validator from the latter slot published theirs, effectively censoring them (exactly the scenario depicted above);

- Always build on the block from the later slot. This way a dishonest validator in slot X can choose to ignore the block published for slot X-1, and be certain the validator in slot X+1 will choose their block, effectively censoring the block in X-1;

- Always build on the block that was received earlier. This way either of the above scenarios are possible if the dishonest validator has better network connection to the validator in the next slot;

- Choose the block randomly. This way dishonest validators can never censor with certainty (unless they have multiple slots in a row), but if censoring has higher value for them than the block reward, can still naturally attempt to censor and have a 50% chance of succeeding.

All of the above scenarios are undesirable.

BFT approaches

A family of proposals that address the issues above use some sort of a BFT consensus algorithm on each block among the validators. One of the earliest papers suggesting such approach is ByzCoin, but a multitude of other protocols were built upon this idea since then.

The main property of such protocols is that once a block was finalized by the committee, for as long as dishonest participants control less than ⅓ of the validators, the block is irreversible, so neither forking nor censoring is possible.

Two major disadvantages are then a) most of the existing BFT algorithms are very slow, and were not designed for a large set of participants trying to reach the consensus, and b) being offline is considered to be adversarial behavior, and thus if less than ⅔ of participants are online, the consensus on the blocks cannot be reached, and the system, at least for some time, stalls.

Attestations

Ethereum 2.0 instead uses the former approach, each time slot having a particular validator who is assigned to create a block at that time slot. Such a validator is called a proposer. However, Ethereum 2.0 extends the approach by encouraging each other validator in the committee to “attest” to the block by signing it. The signatures are accumulated using BLS signatures aggregation, which prevents the block size from exploding with the number of attesters. Moreover, if for a given slot a validator didn’t see the block being produced, or the block was produced on a chain that the validator doesn’t see as the current chain, the validator is encouraged to attest to a so-called “skip-block”. This way an honest validator is expected to attest to exactly one block each time slot, either the actual block produced by a proposer, or a “skip-block”.

By using attesters and a smart fork choice rule Ethereum 2.0 shard chains manage to avoid most of the issues of both vanilla PoS approach and the family of BFT consensus algorithms.

Fork choice rule

To get the selected chain, one starts at the genesis block, and at each step if there’s a fork chooses the block that has the most unique attesters attesting to either that block, or any block in that block’s branch (with a caveat described below in section Latest Message Driven).

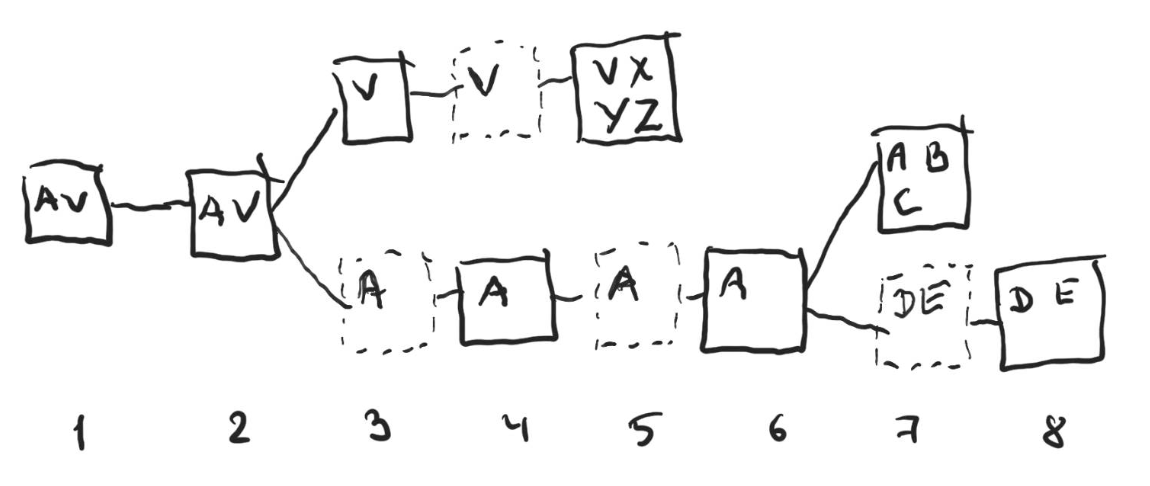

Consider the example above. Letters in each block indicate the names of the attesters on the block. The dashed blocks are skip-blocks. There’s a fork early on, and Alice (A), Bob (B), Carol (C), Dave (D), Elaine (E) have attested to some blocks in the lower branch, while Victor (V), Xavier (X), Yasmine (Y) and Zach (Z) have attested to some blocks in the upper branch.

To find out the selected chain, one starts at the genesis block (slot 1) and moves to the right. At the block in slot 2 the participant has to choose between the upper branch and the lower branch. The fork choice says that the branch with more unique attesters across all the blocks in the branch shall be selected. The lower branch has five unique attesters (Alice, Bob, Carol, Dave and Elaine), while the upper branch only has four (Victor, Xavier, Yasmine and Zach), so the lower branch is chosen. Note that there’s no actual chain in the lower branch that has five attesters attesting to the blocks in it, moreover there’s no chain in the lower branch that has even four unique attesters attesting the blocks in it (the chain that ends in the block at slot 7 has only attestations from Alice, Bob and Carol, while the chain that ends in the block at slot 8 has only attestations from Alice, Dave and Elaine). But accumulated across all the blocks in the lower branch the number of attesters is higher than in the upper branch, and thus the lower branch is chosen.

Similarly, at block in slot 6 one would have to choose between two branches, with the upper branch having attestations from 3 unique attesters (Alice, Bob and Carol) and the lower from only two (Dave and Elaine), thus one would go to the upper branch eventually choosing the chain with blocks in slots 1, 2, 4, 6, 7.

Latest Message Driven

In the present fork choice rule design only the attestation from each attester with the highest slot number is considered. For example, on the figure below Alice attested to a block in slot 3, and only that attestations from Alice is used throughout the fork choice rule. In particular, her attestation in slot 2 is no longer considered, and thus when deciding on the branch at slot 0 the upper chain will be chosen since it has three attestations (Alice, Bob and Elaine), while the lower chain only has two (Carol and Dave):

Note that it doesn’t matter which of the two attestations from Alice was submitted by her first, or in which order the attestations were received by a particular observer, only the attestations with the highest slot number (in this case 3) will be considered.

Attestation conditions

An honest attester must only attest to a block if the following conditions are met:

- The block belongs to the chain that the attester considers to be the currently selected chain;

- The attester hasn’t attested to any other block for the same time slot. Note that honest proposers would never propose two blocks for the same slot, so this rule only kicks in if a malicious proposer attempted to create a fork by producing multiple blocks for the same slot, a condition that is immediately slashable.

If an attester doesn’t receive a block for a particular slot, they attest to a skip-block for that time slot. It is up for the attester to decide how far into the time slot they wait until they decide to stop waiting for the block and attest to the skip block. Danny Ryan suggests for a honest attester to wait until the middle of the time slot, but ultimately they shall do what they believe optimizes for the chance that they will attest to the same block (whether actual or skip-) as the majority of the other attesters.

Analysis

Liveness

Unlike the family of BFT consensus algorithms, the approach discussed above continues to operate even if more than ⅓ of all the validators are offline. The participants in the network will observe that the blocks do not get ⅔ of attestations, and will be more cautious about the finality of the blocks, waiting for additional security (for example by waiting until the block is cross-linked to the beacon chain and is finalized by Casper FFG there, topics outside the scope of this write-up), but importantly, the blocks will continue to be published, and the system doesn’t stall.

Censorship

First observe that of the two censorship scenarios discussed above, the one in which two validators that have two consecutive slots censor out the block in the slot immediately preceding them is no longer valid, since the length of the chain doesn’t affect the fork choice rule any longer.

The second scenario (in which the proposer for a block delays it until the next block is published), would still be possible if the attesters were not required to only attest during the time frame for the corresponding slot: a malicious proposer in time slot X could delay their block until the block X+1 is published, and then publish theirs. The attesters would not be able to distinguish between malicious intent and mere network delay, and without a specific requirement not to attest during the time window for the corresponding slot could still attest to block for slot X, effectively censoring X+1.

The requirement to attest within the time frame completely solves the problem if the clocks among all the participants are perfectly synchronized. If the clocks are not synchronized (but are still within at most couple seconds from each other), some sorts of timing attacks are possible, though are extremely unlikely.

Forkfulness

Between the two possible approaches to how the attesters are accounted for (LMD in which only the largest-slot-number attestation from each attester is considered, and IMD in which all the attestations are considered) the latter provides slightly better forkfulness guarantees (see Forkfulness section in my original write-up here), though still not as good as the family of BFT consensus algorithms.

With the LMD approach that is the current proposal for Ethereum 2.0 described in this write-up the forkfulness is weaker (i.e. forks are more likely). To understand why consider a branch with 60 attestations, some of which are by malicious attesters, and another branch with 40 attestations. In IMD 21 of the attesters who attested to the first branch need to exercise a malicious intent and attest to a block in the competing chain for that chain to beat the selected chain (in the end having 61 attestations vs 60 on the previously selected chain). In LMD it is sufficient for 11 attesters to exercise malicious behavior (in the end having 51 attestations vs 49 on the previously selected chain). Despite this weakness LMD still helps reduce the forkfulness, though does not remove the forks completely, even if more than ⅔ of attestations are accumulated and less than ⅓ of adversaries are present. Consider the following example:

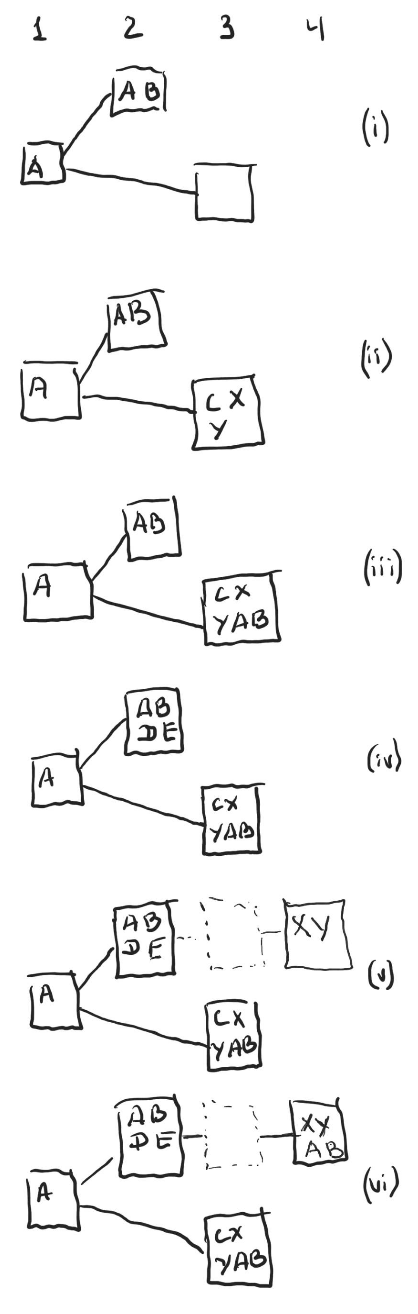

Assume there are 7 validators, Alice (A), Bob (B), Carol (C), Dave (D) and Elaine (E) are honest, while Xavier (X) and Yasmine (Y) are malicious.

(i) There’s a fork with producers for time slot 2 and 3 both building on top of the block in slot 1. Alice and Bob both saw the block in time slot 2 during the time it was published and attested to it;

(ii) Carol saw the block in time slot 3 when it was published, but hasn’t seen the block in slot 2 and its attestations yet, and thus attested to block in slot 3, so did Xavier and Yasmine;

(iii) Now that the block in time slot 3 has three attestations, Alice and Bob consider it to be the selected block and also attest to it (assuming the time for the attestations hasn’t expired yet); The block in time slot 3 at this point has more than ⅔ of all the validators attesting to it and ideally shall not be reversible.

(iv) Unknown to other attesters Dave and Elaine also attested to block in slot 2 back when it was still legal, but their attestations were delayed due to slow network, and were not seen by Alice and Bob previously;

(v) Xavier and Yasmine exercise a malicious intent and build and attest to block in time slot 4 that is built on top of a block in time slot 2. At this point the upper chain has more attestations (Dave, Elaine, Xavier and Yasmine) than the lower chain (Carol, Alice and Bob), and becomes current, even though the lower chain had more than ⅔ attestations previously.

(vi) All honest validators now also attest to the new block in slot 4.

Note that this scenario requires a multitude of unlikely events (such as attestations from Dave and Elaine being delayed, which with hundreds of validators becomes extremely unlikely unless the adversaries control the network communication) and resorting to malicious behavior (Xavier and Yasmine attesting to a block they know is not on the selected chain, but still shows that the attestation framework doesn’t provide theoretical guarantees as strong as the family of BFT consensus algorithms.

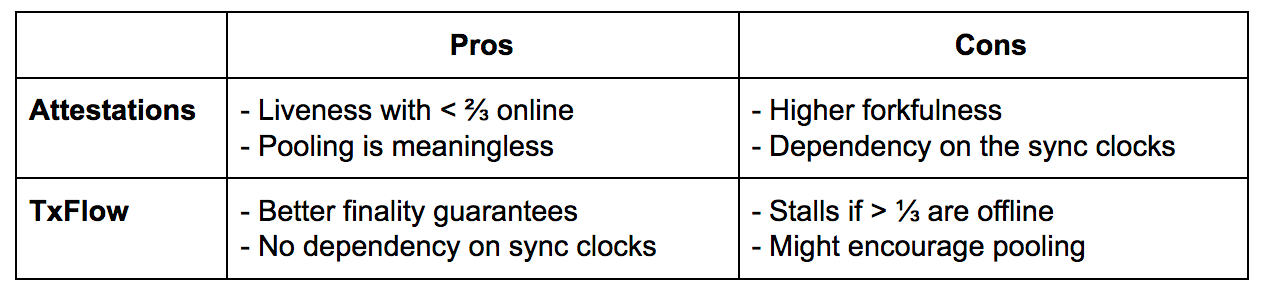

Comparison to TxFlow

TxFlow is a consensus algorithm that NEAR uses for its shard chains. The informal spec of TxFlow can be found here.

The two drawbacks of the Ethereum’s approach are the possibility of forks even after a very large number of attestations and the dependency on synchronized clocks among the validators. In the present proposal blocks are published every 8 seconds, so the clocks need to be synchronized up to several seconds. Simulations ran by the Ethereum Foundation show that even with the clocks discrepancy up to 10 seconds the chain continues to grow. Most of the blocks attested to become skip-blocks, but such skip-blocks point to regular blocks, effectively making the chain of regular blocks continue growing.

TxFlow maintains most of the guarantees and properties of the Ethereum’s approach, but doesn’t have the dependency on the synchronized clocks, and guarantees block irreversibility under an assumption that fewer than ⅓ of all the validators are malicious. In the present design it does, however, lose liveness if more than ⅓ of the validators are offline until the validators are rotated.

Footnote: Note that the assumption of less than ⅓ of malicious validators in a shard is not reasonable when the number of shards is high and the adversaries are adaptive, so the family of BFT protocols including TxFlow are also likely to ultimately have forks.

It is worth pointing out that in the EthResearch thread on TxFlow, Vitalik points out that the TxFlow’s approach to deciding when blocks can be published (which is effectively “as fast as the network allows”) has another drawback, which is that nodes now have an incentive to pool and collocate to reduce the latency between them. The counterargument to this point is that in TxFow the bottleneck on the blocks is the latency of the fastest validator among the slowest ⅓, meaning that unless around ⅔ of all the validators collocate, collocation doesn’t speed up block production (and thus rewards) much. Thus for the collocation and the centralization it brings to occur, a major cooperation among validators is needed, which is extremely unlikely for as long as the pool of the validators is sufficiently large.

The choice between the TxFlow and Attestations framework narrows down to the following table:

Outro

If you are interested in the space of sharded decentralized ledgers, please follow our progress:

- NEAR Twitter — https://twitter.com/nearprotocol,

- My Twitter — https://twitter.com/AlexSkidanov

- Medium — https://medium.com/nearprotocol,

- Discord — https://discord.gg/kRY6AFp,

- Research Forum — http://research.nearprotocol.com

https://upscri.be/633436/

We will also make our primary repository on GitHub open within coming weeks, so stay tuned.

Huge thanks to Vitalik Buterin, Justin Drake and Danny Ryan for answering numerous question and clarifying the attestations framework, and to Bowen Wang and David Stolp for reviewing the draft of this article.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog

NEAR Launches Infrastructure Committee with $4 Million in Funding