Thresholded Proof Of Stake

A central component of any blockchain is the consensus. At its core, Blockchain is a distributed storage system where every member of the network must agree on what information is stored there. A consensus is the protocol by which this agreement is achieved.

The consensus algorithm usually involves:

- Election. How a set of nodes (or single node) is elected at any particular moment to make decisions.

- Agreement. What is the protocol by which the elected set of nodes agrees on the current state of the blockchain and newly added transactions.

In this article, I want to discuss the first part (Election) and leave exact mechanics of agreement to a subsequent article.

Proof of Work:

Examples: Bitcoin, Ethereum

The genius of Nakamoto presented the world with Proof of Work (PoW) consensus. This method allows participants in a large distributed system to identify who the leader is at each point in time. To become a leader, everybody is racing to compute a complex puzzle and whomever gets there first ends up being rewarded. This leader then publishes what they believe is the new state of the network and anybody else can easily prove that leader did this work correctly.

There are three main disadvantages to this method:

- Pooling. Because of the randomness involved with finding the answer to the cryptographic puzzle which solves a given block, it’s beneficial for a large group of independent workers to pool resources and find the answer more predictably. With pooling, if anybody in the pool finds the answer, all members of the pool gets fraction of the reward. This increases likelihood of payout at any given moment even if each reward is much smaller. Unfortunately, pooling leads to centralization. For example it’s known that 53%+ of Bitcoin network is controlled by just 3 pools.

- Forks. Forks are a natural thing in the case of Nakamoto consensus, as there can be multiple entities that found the answer within same few seconds. The fork which is ultimately chosen is that which more other network participants end up adopting. This leads to a longer wait until a transaction can be considered “final”, as one can never be sure that the current last block is the one that most of the network is building on.

- Wasted energy. A huge number of customized machines operate around the world solely performing computations for the sake of identifying who should be the next block leader, consuming more electricity than all of Denmark. Iceland for example spends a significant percentage of all electricity produced on mining Bitcoin.

Proof of Stake.

Examples: EOS, Steemit, Bitshares

The most widely adopted alternative to Proof of Work is Proof of Stake (PoS). As an idea, it means that every node in the system participates in decisions proportionally to the amount of money they have.

One of the main ways of using PoS in practice is called Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS). In this system, the whole network votes for “delegates” — participants who maintain the network and make all of the decisions on behalf of the other members. Depending on the implementation, delegates must either personally stake a large sum of money or use it to campaign for their election. Both of these mean that only high net worth individuals or consortia can be delegates.

In theory, this is very similar to how equity in companies works. In that case, small equity holders participate in elections and elect a small number of decision makers (the board of directors), who are typically large equity holders. These large equity holders then make all of the major decisions on the behalf of all shareholders.

Depending on the specifics of consensus itself, the Proof of Stake system can address the forking and wasted energy that are problematic with Proof of Work. This method still has downside of centralization due to either small number of individual nodes (EOS) or centrally controlled pools end up participating in network maintenance. Also, in specific implementations of DPoS, the fact that all delegates know each other means that slashing (penalizing delegate for wrongdoing by taking their stake) may not happen because a majority of delegates must vote for it.

Ultimately, these factors mean that a small club of rich get richer, perpetuating some of the systemic problems that blockchains were created to address.

Thresholded Proof Of Stake:

Examples: NEAR

NEAR uses an election mechanism called Thresholded Proof of Stake (TPoS). The general idea is that we want a deterministic way to have a large number of participants that are maintaining network maintenance thereby increasing decentralization, security and establishes fair reward distribution. The closest alternative to our method is an auction, where people bid for fixed number of items and at the end the top N bids win, while receiving a number of items proportional to the size of their bids.

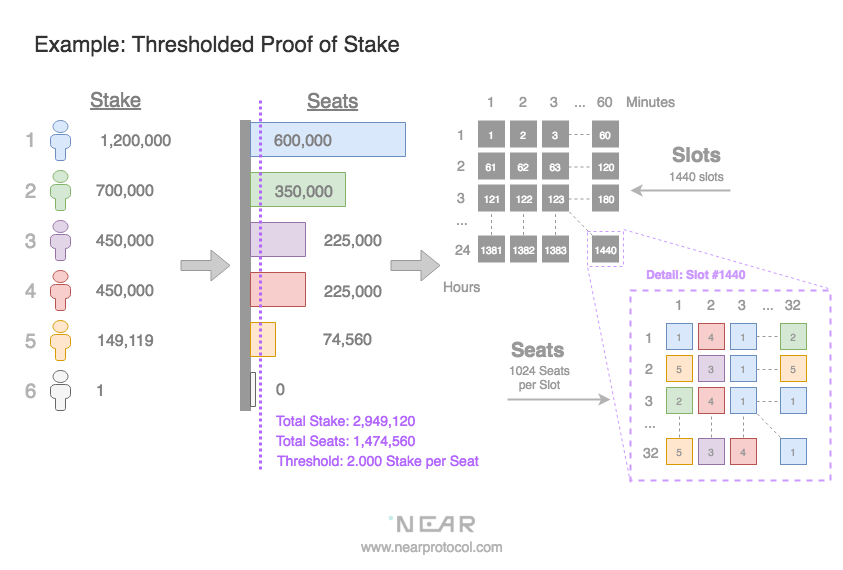

In our case, we want a large pool of participants (we call them “witnesses”) to be elected to make decisions during a specific interval of time (we default to one day). Each interval is split into a large number of block slots (we default to 1440 slots, one every minute) with a reasonably large number of witnesses per each block (default to 1024). With these defaults, we end up needing to fill 1,474,560 individual witness seats.

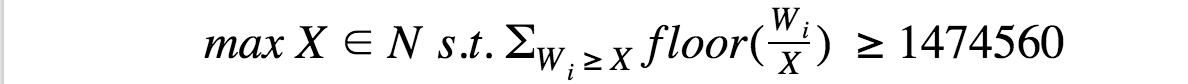

Each witness seat is defined by the stake of all participants that indicated they want to be signing blocks. For example, if 1,474,560 participants stake 10 tokens each, then each individual seat is worth 10 tokens and each participant will have one seat. Alternatively, if 10 participants stake 1,474,560 tokens each, individual seat still cost 10 tokens and each participant is awarded with 147,456 seats. Formally, if X is the seat price and {Wi} are stakes by each individual participant:

To participate in the network maintenance (become a witness), any account can submit a special transaction that indicates how much money one wants to stake. As soon as that transaction is accepted, the specified amount of money is locked for at least 3 days. At the end of the day, all of the new witness proposals are collected together with all of the participants who signed blocks during the day. From there, we identify the cost for an individual seat (with the formula above), allocate a number of seats for everybody who has staked at least that amount and perform pseudorandom permutation.

NEAR Protocol uses inflationary block rewards and transaction fees to incentivize witnesses to participate in signing blocks. Specifically, we propose an inflation rate to be defined as percentage of total number of tokens. This encourages HODLers to run participating node to maintain their share in the network value.

When participant signs up to be witness, the portion of their money is locked and can not be spend. The stake of each witness is unlocked a day after the witness stops participating in the block signature. If during this time witness signed two competing blocks, their stake will be forfeited toward the participant that noticed and proved “double sign”.

The main advantages of this mechanism for electing witnesses are:

- No pooling necessary. There is no reason to pool stake or computational resources because the reward is directly proportional to the stake. Put another way, two accounts holding 10 tokens each will give the same return as 20 tokens in a single account. The only exception if you have less tokens then threshold, which is counteracted by a very large number of witnesses elected.

- Less Forking. Forks are possible only when there is a serious network split (when less then ⅓ adversaries present). In normal operation, a user can observe the number of signatures on the block and, if there is more than ⅔+1, the block is irreversible. In the case of a network split, the participants can clearly observe the split by understanding how many signatures there are versus how many there should be. For example, if the network forks then the majority of the network participants will observe blocks with less than ⅔ (but likely more than ½) of necessary signatures and can choose to wait for a sufficient number of blocks before concluding that the block in the past is unlikely to be reversed. The minority of the network participants will see blocks with less than ½ signatures, and will have a clear evidence that the network split might be in effect, and will know that their blocks are likely to be overwritten and should not be used for finality.

- Security. Rewriting a single block or performing a long range attack is extremely hard to do since one must get the private keys from witnesses who hold ⅔ of total stake amount over the two days in the past. This is with assumption that each witness participated only for one day, which will rarely happen due to economic incentive to continuously participate if they holding tokens on the account.

A few disadvantages of this approach:

- Witnesses are known well in advance so an attacker could try to DDoS them. In our case, this is very difficult because a large portion of witnesses will be on mobile phones behind NATs and not accepting incoming connections. Attacking specific relays will just lead to affected mobile phones reconnecting to their peers.

- In PoS, total reward is divided between current pool of witnesses, which makes it slightly unfavorable for them to include new witnesses. In our approach we add extra incentives for inclusion of new witness transactions into the block.

This system is a framework which can incorporate a number of other improvements as well. We are particularly excited about Dfinity and AlgoRand’s research into using Verifiable Random Functions to select random subset of witnesses for producing next block, which helps with protecting from DDoS and reducing the requirement to keep track of who is a witness at a particular time.

In future posts of this series, we will discuss the Agreement part of our consensus algorithm, sharding of state and transactions and design of distributed smart contracts.

To follow our progress you can use:

- Twitter — https://twitter.com/nearprotocol

- Discord — https://near.chat

https://upscri.be/633436/

Thanks to Ivan Bogatyy for feedback on the draft. Thanks to Alexander Skidanov, Maksym Zavershynskyi, Erik Trautman, Aliaksandr Hudzilin, Bowen Wang for helping putting together this post.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog

NEAR Launches Infrastructure Committee with $4 Million in Funding